F.001

F.001

F.002

F.002

F.003

F.003

F.004

F.004

F.005

F.005

F.006

F.006

F.007

F.007

F.008

F.008

F.009

F.009

F.010

F.010

F.011

F.011

W.004

The Routledge Companion to Design Research

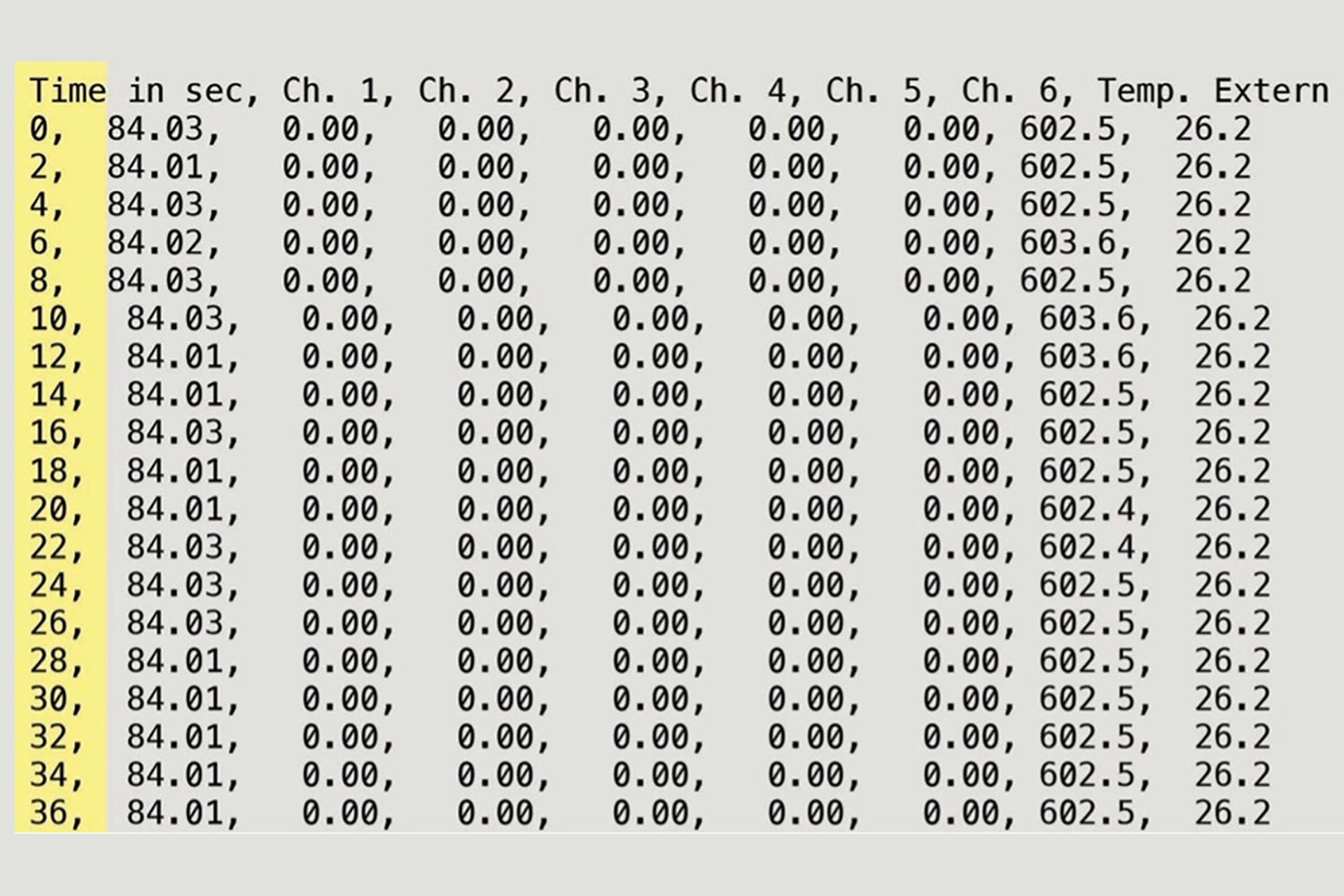

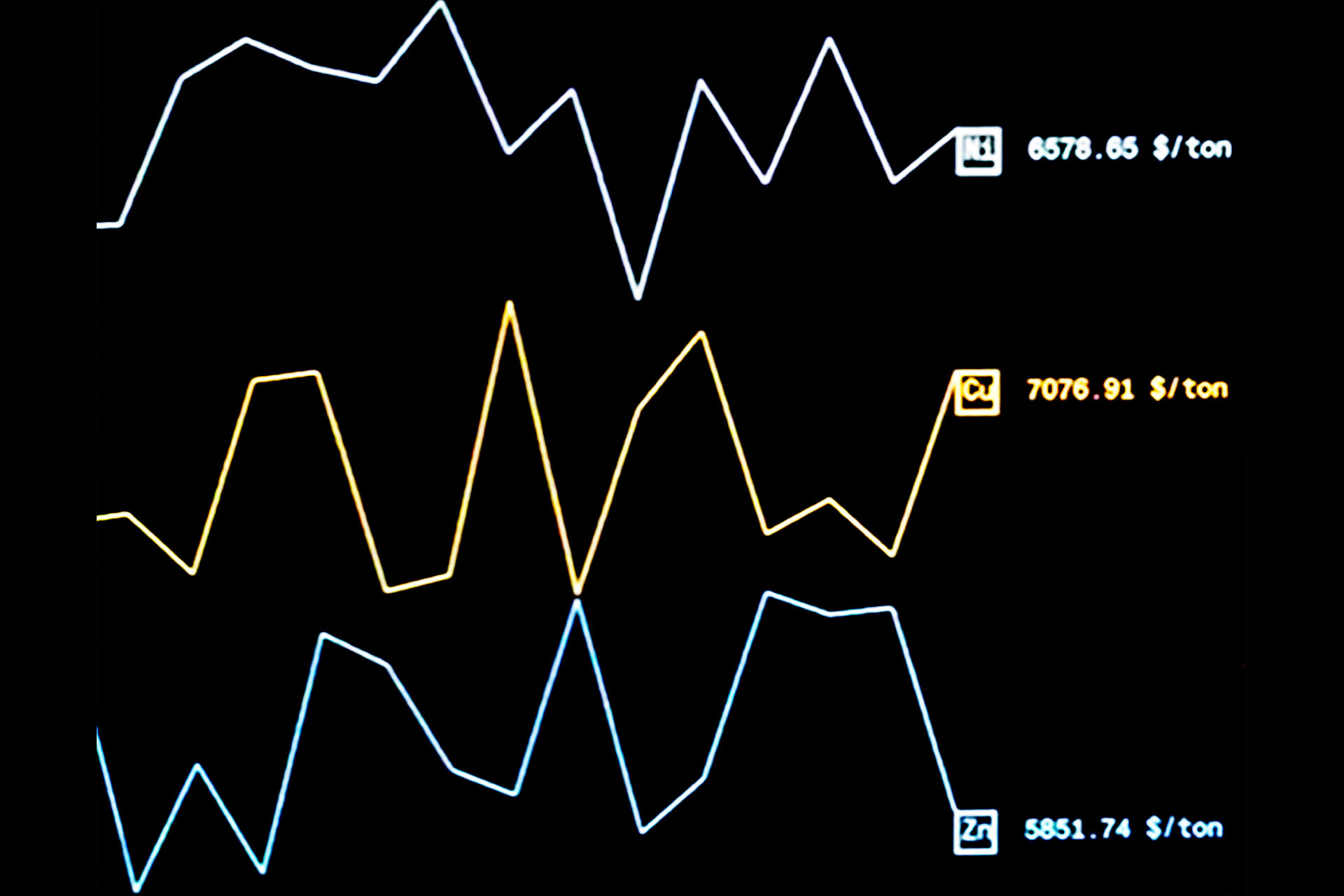

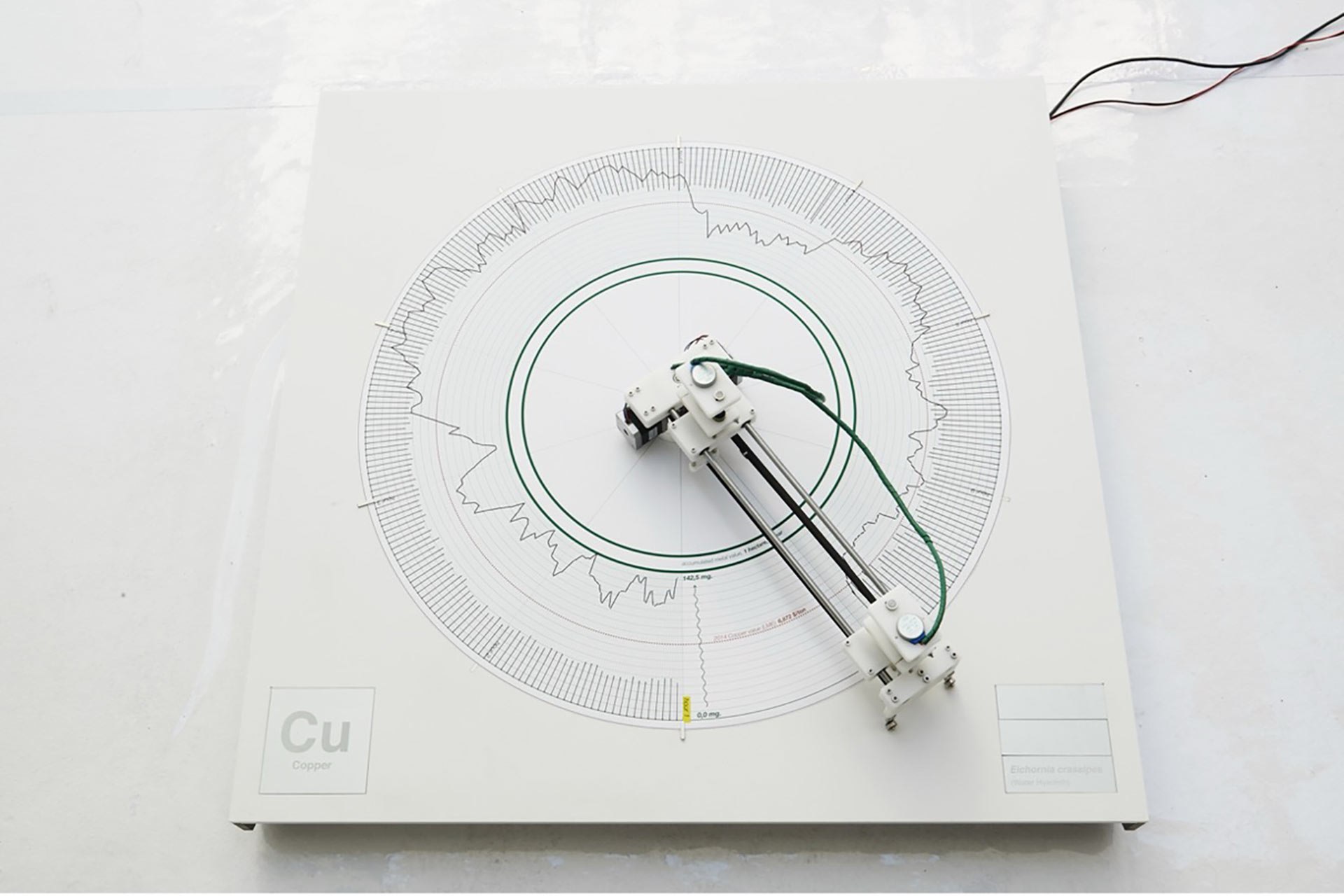

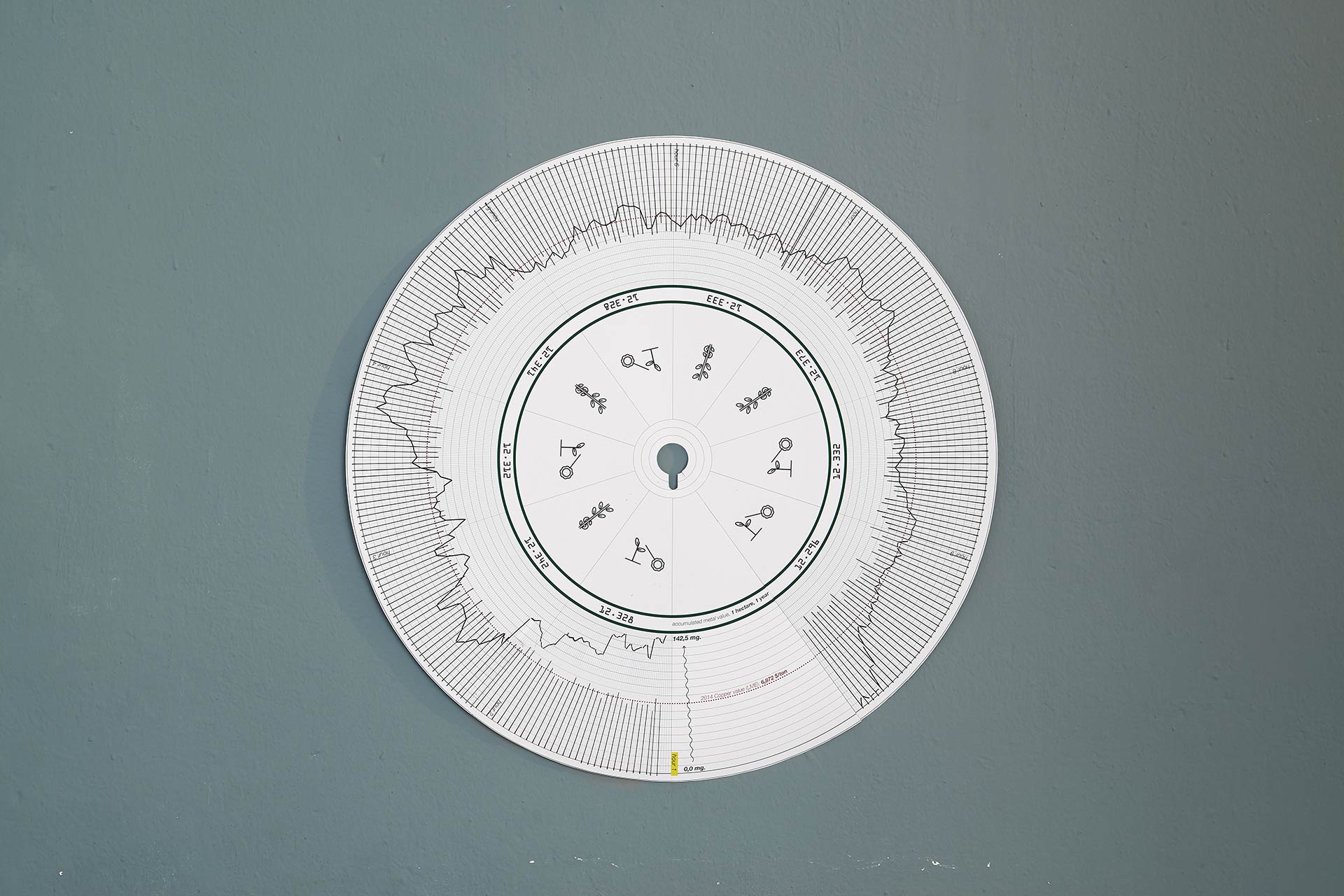

GeoMerce: Speculative relationships between nature, technology and capitalism

This paper chronicles and reflects on the processes and the meanings of a project titled GeoMerce. GeoMerce is a project of speculative design that creates a narrative based on the scientific notion of phytomining, the activity of extracting metals from the soil using plants. The narrative of the project generates a scenario in which agriculture and finance blend with each other. The project brought together a diverse network of professionals ranging from biologists, technologists, financial advisors, tinkerers, videomakers, enabling an exchange of voices that otherwise would have not occurred. Besides the scientific and technical challenges posed by GeoMerce, the authors of this paper reflect on the critical framework that set the basis for such a complex project. In fact, while GeoMerce seems to hint at the possibility of a bright and positive future, it also casts the shadows of a dystopian scenario in which financial profit and actual or speculative monetary value determine every aspect of our world, including nature and our relationship with it. In this sense, GeoMerce serves as a trojan horse that first seduces the viewer with the promises of a rising Green Capitalism; while on the other hand it reveals the horror of a world where nature is just another financial asset.

Words

I would like to thank: Stimuleringsfunds Creative Industries; Giovanni Innella; the Plant Sciences and Environmental Sciences group of the University of Wageningen. This book chapter partially builds on work previously presented at conference: The Ecological Turn, January 2021. Another version was presented at conference: Safe Harbors, October 2021.

References

Ascott, R., 2000. Edge-Life: Technoetic Structures And Moist Media, in: Ascott, R. (Ed.), Art, Technology, Consciousness: Mind@Large. Intellect, Bristol, UK, pp. 2–6.

Gatto, G., 2020. Design as Multispecies Encounter: Plant Participation and Agency In and Through Speculative Design. Loughborough University.

Gatto, G., McCardle, J.R., 2019. Multispecies Design and Ethnographic Practice : Following Other-Than-Humans as a Mode of Exploring Environmental Issues. Sustainability.

Haraway, D., 1988. Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies 14, 575.

Irwin, T., 2015. Transition Design: A Proposal for a New Area of Design Practice, Study, and Research. null 7, 229–246.

Koskinen, I., Zimmerman, J., Binder, T., Redstrom, J., Wensveen, S., 2011. Design research through practice: From the lab, field, and showroom. Elsevier.

Moore, M.J., Cullen, U., 1995. Speculative efficiency on the London metal exchange. The Manchester School of Economic & Social Studies 63, 235–256.

O’Brien, L., Marzano, M., White, R.M., 2013. “Participatory interdisciplinarity”: Towards the integration of disciplinary diversity with stakeholder engagement for new models of knowledge production. Science and Public Policy 40, 51–61.

Santachiara, D., Montedison, S.p.A (Eds.), 1985. La Neomerce: il design dell’invenzione e dell’estasi artificiale, Quaderni della Triennale. Presented at the Triennale di Milano, Electa, Milano.

Smith, R., 2016. Green capitalism: the god that failed. College Publications on behalf of the World Economics Association, Milton Keynes.

Steinberg, S.L., Steinberg, S.J., 2015. GIS research methods: incorporating spatial perspectives.

Sullivan, S., 2009. Green capitalism, and the cultural poverty of constructing nature as service-provider. Radical anthropology 3, 18–27.

Visioli, G., Vincenzi, S., Marmiroli, M., Marmiroli, N., 2012. Correlation between phenotype and proteome in the Ni hyperaccumulator Noccaea caerulescens subsp. caerulescens. Environmental and Experimental Botany 77, 156–164.

Wood, S.A., Samson, I.M., 1998. Solubility of Ore Minerals and Complexation of Ore Metals in Hydrothermal Solutions, in: Reviews in Economic Geology. Society of Economic Geologists, pp. 33–80.

Team

Design & concept

Giovanni Innella; Gionata Gatto

Methodology

Giovanni Innella; Gionata Gatto

Writing

Giovanni Innella; Gionata Gatto

Review

Giovanni Innella; Gionata Gatto